Here is a paper I wrote a few months ago for my Tae Kwon Do instructor. My theory on forms. If you stop most people on the street and ask them what they know about martial arts, their response would be something along the lines of, “It is a way to beat people up, like Bruce Lee right?” It is unfortunate that most people view martial arts as only a way to beat people up and not as a self defense, a meditation, and a look into yourself. Most think of forms as a formality, a tedious exercise devised for the sole purpose of learning the technique so it can later be translated into sparring and demonstration. While there are schools that exist who teach forms solely for that purpose, it is not the true purpose of a form.

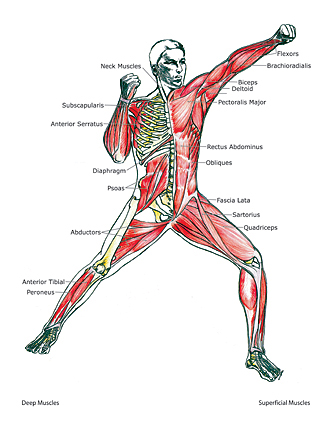

In the world of martial arts forms serve many purposes. They can be used to learn and build technique, as I have stated, but they are also meant to be a workout, a skill check, and above all, a moving meditation. A form is a way of feeling your entire body working as a whole. When you practice pure technique, you get the physical workout without the mental. In a form you keep your focus straight forward, letting nothing distract you, absorbed in the form and only the form. This causes your body and mind to work as one.

I was told by my grand master, Master Chaney, that if one were to do all of their forms from start to finish with a good pace while keeping all of your focus on the form, nothing else in your mind but that, you will receive a better workout than if you had sparred for the same amount of time. Sparring, while delivering a great physical workout, does not put you in the same state of calm forms do. If done properly, forms will relax your mind and calm your body, readying you for whatever stressful activity may follow. Before each of my belt tests I do all of my forms, from first to last, without stopping and with all the focus I can muster. The state I am put in as a result causes me to perform at a heightened level than had I not.

When stress hits in your life, some tend to grow angry or tense. They turn to violence as opposed to turning to meditation and calming action. When I become stressed I go through my forms over and over until I am too exhausted to continue with my stress. The forms put everything in perspective. With my mind calmed I can focus on what I need to do to relieve the stress and then more easily accomplish it.

Forms have many practical applications outside the dojo. However, they are just as important inside. Forms promote the understanding of technique and the refinement of movement. While practicing a form one can understand where each technique is intended to strike or block, and refine the movement until it becomes second nature. If you were to take a white belt and never teach them any forms, just the basic movement, then tell them to practice them until they were satisfactory, it would be a feat consuming much of their time. With a form, a beginner, as well as advanced students, can focus on one particular set of movements and refine those few techniques. In the beginning forms you face all directions. You learn to turn, perform techniques with either hand dominant, and move your body as a whole. The power of a strike is worthless if your feet are not planted on the ground and your body is not ready to absorb the impact. Forms teach students these lessons on their own time.

The form is completed at different paces for each person, and that is the beauty of it. The longer you work on a form the more you can begin to focus on what every part of your body is doing. You can begin setting your hands and feet at the same time, turning your head before you turn your body, and keeping your head at one level throughout, thus improving stances. Forms contain different stances for just that purpose. To be an effective martial artist you must know how to fight and perform in all ways, know which techniques require which stance to achieve their full effectiveness, and how to perform the stance to obtain full stability. No matter how long you work on a form there is always something in it that needs improvement. If asked the question, “Which form are you the best at?” there are some who would respond with which form is their favorite. This is not the proper answer to this question. While there are exceptions, the form that most are best at is the first one they learned. You have been practicing your first form since day one and, ideally, each day since. With that much worked poured into a form it is sure to be the one you have refined and perfected the most of all of your forms.

I was once asked if I would rather be a willow tree or an oak in a storm. The oak, standing proud and tall can try to weather the storm, fighting to stay upright while the elements pound at its body. The willow will flow with the wind, be moved by the rain, and never snap under the pressure. I think about this every time I do a form. One must go with the flow of the form and not try to power your way through it. Many techniques in forms flow into each other and are not meant to be separated by breaks or pauses. In the same respect, when the question of my preference between a river, the mountain above the river, or a pebble in the river arose, my answer was clear. The mountain will hold its ground for many lifetimes, but the river will erode it. The pebble will be tossed about in the river and slowly get worn into nothing, but the river will always remain. Water flows past obstacles without so much as a glance backwards. It adapts to any situation without trouble and cannot be contained forever.

To execute a form with its full fluidity and beauty, one must be confident in their ability to feel the form. That is, to execute the form without the use of all of their senses. For my red belt testing I was required to do all of my forms while blindfolded. Without the use of my vision I was disoriented and confused. As I began the form I stopped trying to see and started to feel. I could feel my foot turning on the ground, and from that decide how far I needed to turn, I could feel my arms in relation to my core, and from that decide where they needed to be placed, and I could feel my body moving as one. It was this experience that caused me to begin focusing more and more on my forms and to worry less about the “beat up the bad guys” approach to martial arts.

Forms teach us how to move, where to move, and when. They calm our bodies and our minds as we flow through them. They illustrate the necessity for adaptation to situation and the superiority of fluidity over rigidity. They make you analyze every technique you execute, questioning why you do it, how it is done properly, and where it is aiming. Always questioning. Forms raise questions as much as they answer them, and through the further practice and study of forms, the questions are slowly answered, only to raise more questions. Without questions we wouldn’t need masters, and then where would we be? Without the forms forcing us to question all aspects of what we do, we would all have the “beat up the bad guys” mindset that seems so common in those who do not practice martial arts, or those who practice it solely for that purpose. With the mental power forms provide, one can overcome any physical obstacle put in their way. With a strong mind and a strong body, the largest obstacles shrink.

__________________________

__________________________